Anti-doping rules could indeed prove excessive by virtue of, amongst others, ‘the severity of (...) penalties.’1

Introduction

‘The period of ineligibility shall be four years.’2 The most significant change between the 2009 World Anti-Doping Code (WADA Code) and the 2015 WADA Code was the prolongation of the default period of ineligibility for the first anti-doping rule violation from two to four years. According to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), there was a strong consensus amongst stakeholders that those who intentionally break the rules should be ineligible for a period of four years. Especially athletes sought to punish real cheaters more severely.3 At the same time, they aimed at deterring athletes and other persons from taking prohibited substances and using prohibited methods. Furthermore, WADA argues that there is a broad support for the four-year sanction for intentional doping.4

I believe, however, that athletes might have set the trap for themselves by arguing in favour of increasing the length of the sentence. I understand the desire of clean athletes to punish intentional cheaters. Nevertheless, there is a thin line between lawful ways of enhancing one’s performance one on hand and prohibited conduct on the other hand. In other words, it is sometimes very easy to fall within a doping trap.5 Moreover, there are doubts about the extent to which anti-doping regulations comply with the right to a fair trial, presumption of innocence and other human rights of athletes.6 To sum it up, I am not sure whether athletes promoting harder punishment thought in detail about possible negative consequences that such a sanction might aptly have for their lives.

Be it as it may, while a four-year period of ineligibility punishes cheater more severely, I argue in this essay that its capacity to deter athletes from violating rules is at least doubtful. More seriously, I claim that it constitutes a disproportionate restriction on the rights that athletes derive from European Union (EU) law as EU citizens, workers, self-employed persons or undertakings. Under EU law, athletes have, in general, a right to move freely between EU member states in order to pursue an economic activity and to engage in fair economic competition. However, a four-year ban prevents athletes from practising their sport for an unreasonably long period and therefore averts their rights under EU law. I think that the otherwise legitimate objectives of protecting the athletes’ fundamental right to participate in doping-free sport and thus promoting health, fairness and equality for athletes worldwide7 do not justify such a severe punishment and restriction on athletes’ rights.

I am aware of the WADA’s claim that ‘the WADA Code has been drafted giving consideration to the principles of proportionality and human rights’8 and that the WADA Code proceedings are ‘intended to be applied in a manner which respects the principles of proportionality and human rights.’9 I respect the legal opinion of a French jurist and former President of the European Court of Human Rights Jean-Paul Costa, who sanctified the WADA Code, including the sanctions, from the perspective of the accepted principles of proportionality and human rights.10 Nevertheless, I believe that the period of ineligibility establishes an imbalance between WADA’ interests and values enshrined in a four-year period of ineligibility on one hand, and athletes’ rights under EU law on the other hand.

Therefore, I simultaneously try to find an ideal model formulating concrete recommendations for WADA and sporting governing bodies in order to better adapt the WADA Code and their rules to EU law requirements. Namely, I suggest a set-back to 2009 and the decrease of the default period of ineligibility from four to two years with the possibility to apply the four-year ban only in exceptional circumstances when aggravating circumstances occur. Simultaneously, I believe that WADA as well as other sporting actors should pay more attention to prevention and the dissemination of anti-doping knowledge amongst athletes rather than to focus on toughening the punishment and highlighting the deterrence effect.

In order to justify the aforementioned conclusions, I divide this essay into two parts. I initially examine the development and the current system of the period of ineligibility in the WADA Code. To eliminate all initial doubts, I do not examine the legality of sanctions in concrete cases within the scale offered by various WADA Code provisions. Rather, I focus on the general four-year period of ineligibility, which I consider illegal as such (Chapter 1). Thereafter, I dive into the analysis of the compliance of a four-year period of ineligibility with various provisions of EU law concerning EU citizenship, free movement of persons and competition. I focus on the principle of proportionality, which is, in my opinion, the decisive element (Chapter 2).

1. Period of ineligibility in the World Anti-Doping Code

In this chapter, I explore a four-year period of ineligibility as a sanction for anti-doping rules violation. I firstly map the development of a period of ineligibility in the history of the WADA Code in order to show WADA’s tendency of prolonging the period of ineligibility imposed for various breaches of anti-doping rules. Consequently, I focus on the nowadays applicable 2015 WADA Code and its system of sanctions, namely the periods of ineligibility. My goal is to explore the objectives that a four-year period of ineligibility follows in order to prepare the ground for the analysis of the compliance of this sanction with rights that athletes derive from EU law.

The WADA was established on 10 November 1999 in Lausanne in order to promote and coordinate the fight against doping in sport internationally.11 For this purpose, the WADA adopted the WADA Code for the first time in 2003, which entered into force on 1 January 2004, and brought consistency into a previously disjointed and uncoordinated anti-doping system. Since then, the WADA Code has been revised twice. The first amendment was approved on 2007 and entered into force as of 1 January 2009. The current version of the WADA Code was enacted on 15 November 2013 and it is binding as of 1 January 2015.12

The period of ineligibility is usually the most significant negative consequence for a doped athlete. An athlete serving such a penalty is not limited only by the fact that he can’t participate in basically any official competition or sporting activity. She or he can’t even train with a team or use facilities of a club or member organization of the WADA Code’s signatory’s member organization. Moreover, some or all sport-related financial support or other benefits received by the doped athlete are withheld. To sum it up, an athlete is without the possibility to compete and train with during the period of ineligibility while his possibilities concerning financial support are limited.13

The WADA Code’s history shows a tightening tendency regarding the period of ineligibility. Under the 2003 WADA Code, the ban for the first anti-doping rules violation was generally set up for two years. If an athlete could establish that the use of a specified substance was not intended to enhance his sport performance, the period of ineligibility was one year in maximum.14 In the 2009 WADA Code, the general period of ineligibility stayed on two years, but respective bodies could impose a four-year period of ineligibility in a case of ‘aggravating circumstances.’ Nevertheless, this provision was used rarely during the six years of its applicability.15 In the case of specified substances, the maximum sanction was increased to two years, but the athlete must have established not only that specified substance was not intended to enhance the sport performance, but also that it was not intended to mask the use of a performance-enhancing substance. Moreover, he must have showed how a specified substance entered his body.16

In the 2015 WADA Code, the general period of ineligibility was increased to four years for both unspecified and specified substances. ‘There was a strong consensus among stakeholders, and in particular, athletes, that intentional cheaters should be ineligible for a period of four years.’17In the case of unspecified substances, the period of ineligibility is four years long unless the athlete can establish that the anti-doping rule violation was not intentional. In the case of specified substances, it is the anti-doping organization which has to establish that the violation was intentional in order for the four-year period of ineligibility to be imposed. If a four-year period of ineligibility is not used, the period of ineligibility shall usually be two years.18

In the light of the aforementioned, there is a clear tendency of prolonging the period of ineligibility while the distinction between specified and unspecified substances is getting less and less important. Even though the described tendency is not explained in detail in any formal document to my knowledge, I believe that it follows two basic objectives. Firstly, it seeks to deter clean athletes from violating anti-doping rules under a threat of a severe sanction. Second, it tends to punish harder ‘real cheats’.19 I believe that these objectives, as well as the general objective of anti-doping rules to protect the athletes’ fundamental right to participate in doping-free sport and thus promoting health, fairness and equality for athletes worldwide20 are logic and legitimate.

Nevertheless, I claim and I will further explain why a four-year period of ineligibility is not suitable to achieve these objectives and that the restrictive measures of the sanction are disproportionate. While ‘the 2015 WADA Code has the potential to become the fairest WADA WADA Code to date (...), it also has the potential to be the cruelest.’21 For the purpose of this essay, I will focus on a four-year period of ineligibility used in the 2015 WADA Code as a default sanction for presence, use or attempted use, or possession of prohibited substances and use of prohibited methods.22 I am are aware of special circumstances which may result in reduction or even elimination of the period of ineligibility imposed in concrete cases. However, I will show that the quite often imposed four-year ban is illegal under EU law as such even without considering an athlete’s fault (Chapter 2).

2. Four-year period of ineligibility in the context of EU law

It is just the EU where athletes often contest international sporting governing bodies’ rules before administrative bodies and courts. The reason is that beyond rights guaranteed by national laws of their member states, athletes enjoy the rights conferred upon them by the EU legal order. When disputing sporting rules, such athletes often raise arguments stemming from their rights as EU citizens, workers, self-employed persons or undertakings. In this respect, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the European Commission have developed a rich line of sports-related case law, which has had great influence on the whole sporting world.23

When assessing the compliance of sporting rules, including those on anti-doping, with EU law, the CJEU, the European Commission and other EU bodies and institutions follow, in a simplified way, a three-step test, which is generally used for an assessment of compliance of any measure with EU law in the internal market.24 They firstly consider whether sporting rules fall within the scope of EU law (Chapter 2.1). If so, they then assess whether these rules constitute a restriction to the citizenship, free movement and competition law provisions (Chapter 2.2). Thirdly, they examine justification and the proportionality of the restrictions (Chapter 2.3).25 I believe that the EU bodies and institutions would engage in the same analysis when dealing with anti-doping rules since they apply a very similar approach to all sporting rules without greatly distinguishing their specificities.26

2.1. Does EU law apply to anti-doping rules?

In this section, I will show that EU law applies to anti-doping rules in general and sanctions for anti-doping rules violations in particular. While the ECJ had not had the opportunity to rule on anti-doping rules till 2006, it explicitly applied EU competition law as well as rules on free movement of persons to anti-doping regulation in Meca-Medina & Majcen.27 The case concerned two professional long-distance swimmers, David Meca Medina and Igor Majcen, who tested positive for Nandrolon at the World Cup in long-distance swimming at Salvador de Bahia in Brazil in 1999. The FINA’s Doping Panel and consequently the CAS suspended both swimmers for a period of four years.28 Later, the CAS panel reduced the period of ineligibility for both swimmers to two years.29

The two swimmers filed a complaint with the European Commission on 30 May 2001. They challenged the compatibility of the anti-doping regulations adopted by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and implemented by the Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA) and certain related practices with EU law. Namely, they claimed violation of the rules on competition guaranteed by present Arts. 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and the freedom to provide services under Art. 56 and the following TFEU.30 Having analysed the anti-doping rules at issue, the European Commission rejected the swimmers’ complaint by decision of 1 August 2002 stating that, in overall, those rules did not fall foul of the prohibition under Arts. 56, 101 and 102 TFEU.

It is interesting to note, however, that the European Commission analysed in detail the compatibility of the contested anti-doping regulation with the respective TFEU provisions. Therefore, the European Commission implicitly acknowledged that the anti-doping regulations fall within the scope of EU law. And it did it again, this time explicitly, in a 2009 case concerning professional tennis players.31 In Meca-Medina and Majcen, the European Commission nevertheless concluded that the contested anti-doping regulations relate to the progress of sporting competitions, that they are necessary for the effective fight against doping and that the limitation to athletes’ freedom of action does not go beyond what is necessary in order to achieve their objective.32

The swimmers appealed to what was then the Court of First Instance (Tribunal) and asked for the annulment of the European Commission’s decision. While quoting the case law of the Court of Justice (ECJ), the Court of First Instance observed that the provisions of the Treaties regarding the freedom of movement for workers and the freedom to provide services ‘do not affect purely sporting rules, that is to say rules relating to questions of purely sporting interest and, as such, having nothing to do with economic activity.’33 The Court of First Instance continued that the prohibition of doping leans on purely sporting considerations, has nothing to do with any economic consideration and that the rules to combat doping consequently do not fall within the scope of EU law.34 Therefore, the Court of First Instance dismissed the swimmers’ action.35

David Meca Medina and Igor Majcen continued on their legal challenge and appealed to the ECJ.36 Before the ruling, Advocate General Léger delivered his opinion and proposed to reject the appeal, which he described as ‘muddled’. He concluded that the anti-doping regulations concerned the ethical aspects of sport and were not subject to the prohibitions of EU law, even if they had some ancillary economic consequence.37 G. Infantino, the current president of the FIFA, submits that the Advocate General was aware of the fact that high-level sport could involve big money, but it did not mean that sports rules, such as anti-doping rules, fell within the rigours of EU law since any economic aspect of the rules was clearly secondary to their sporting aspect.38

The ECJ, however, took a stricter line. Following its judgment in Donà,39 it addressed the difficulty of severing the economic aspects from the sporting aspects of a sporting activity. It concluded that the provisions of EU law determining the freedom of movement for persons and the freedom to provide services ‘do not preclude rules or practices justified on non-economic grounds which relate to the particular nature and context of certain sporting events.’40 On the other hand, the ECJ underlined that such a restriction on the scope of EU law must remain limited to its proper objective. Therefore, international sporting governing bodies cannot rely on such a restriction ‘to exclude the whole of a sporting activity from the scope of the Treaty.41

This is where the judgment’s contribution comes. Taking into account the foregoing, the ECJ further specified that ‘the mere fact that a rule is purely sporting in nature does not have the effect of removing from the scope of the Treaty the person engaging in the activity governed by that rule or the body which has laid it down.’42 From that point on, EU law applies even to athletes or other persons acting under a purely sporting rule as well as to sporting governing bodies as their authors.43 In Meca-Medina and Majcen, the ECJ consequently applied EU law to anti-doping rules, which the European Commission later repeated in a case concerning professional tennis players.44

It was thought that, a sporting rule which had an economic effect was immune from EU law merely because it was a sporting rule before Meca-Medina & Majcen. Currently, sporting governing bodies will have to show that any sporting rule, which restricts competition or the free movement of persons, has effects which are proportionate to its legitimate aims. I believe that, in this matter, the ECJ’s judgment in Meca-Medina & Majcen represents a good step towards better and more flexible assessment of the compatibility of sporting rules with EU law. Since the purely sporting and the economic elements of sporting rules are in practice hardly differentiable to automatically conclude on the inapplicability of EU law to these rules,45 I believe that it is more suitable to take the purely sporting nature of a rule into consideration when justifying a potential restriction to EU law rather than to exclude automatically the rule from the material scope of EU law.

Recent decision of the European Commission on eligibility rules of the International Skating Union (ISU) does not compromise the applicability of EU law to anti-doping rules. The European Commission has decided that rules imposing severe penalties on athletes participating in speed skating competitions that are not authorised by the ISU are in breach of EU competition law.46 In an official statement following the decision, the Commissioner Vestager said that while the eligibility rules at stake fall foul of EU competition law, ‘there are many disputes which have little or nothing at all to do with competition rules. Things like the penalties for doping or match-fixing, or deciding the precise scheduling of games.’47 Nevertheless, I think that the ECJ made it clear in Meca-Medina & Majcen that EU law, including competition rules, apply to anti-doping regulations.48

In Meca-Medina & Majcen, the ECJ also clarified the test of the compliance of a sporting rule with EU law. Once the sporting activity is subject to EU law, ‘the conditions for engaging in it are then subject to all the obligations which result from the various provisions of (EU law).’49 Therefore, the rules governing the sporting activity in question, namely anti-doping regulations, must satisfy ‘the requirements of those provisions, which, in particular, seek to ensure freedom of movement for workers, freedom of establishment, freedom to provide services, or competition.’50 Therefore, even though this particular case concerned the compliance of anti-doping regulations with EU competition law, its outcomes are similarly applicable to other branches of EU law, notably the free movement provisions.

In the light of the foregoing, I submit that anti-doping rules in general and a period of ineligibility imposed for doping offences in particular may fall under various provisions of EU law protecting namely the free movement of workers, freedom to provide services, freedom of establishment and competition. I will now shift to the question of whether these rules, and in particular a four-year period of ineligibility, constitute a restriction on the rights that athletes derive from EU law as EU citizens, workers, service providers, self-employed persons or undertakings.

2.2. Does a four-year period of ineligibility constitute a restriction to athletes’ rights under EU law?

I claim that anti-doping rules constitute a restriction to the rights that athletes derive from the aforementioned provisions of EU law. According to the case law of the ECJ, the concept of a limitation, an obstacle or a restriction to EU law is very broad and covers a wide group of measures including sporting rules.51 In Meca-Medina & Majcen, the ECJ recognised that the contested anti-doping regulations restrict the athletes’ freedom of action thus limiting their rights under EU law.52 More particularly, the threshold of Nandrolone, which, when exceeded, constitutes a violation of the anti-doping regulations, imposes a restriction on professional sportsmen.53

I submit that a four-year period of ineligibility restricts athletes’ rights and freedoms under EU law as well. The ECJ ruled that anti-doping rules could indeed prove excessive by virtue of, amongst others, ‘the severity of (...) penalties.’54 In this respect, the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland recognized that even a two-year ban results in a restriction of athletes’ freedom of movement which may adversely affect their international careers as top-level competitors.55 During a period of ineligibility, an athlete’s economic and other rights and freedoms under EU law are limited primarily by the fact that he or she can’t participate in basically any official competition or sporting activity. He can’t even train with a team or use facilities of a club or member organization of the WADA Code’s signatory’s member organization. Lastly, some or all sport-related financial support or other benefits received by the doped athlete are withheld.56 Therefore, a four-year period of ineligibility restricts athletes’ rights under EU law.

2.3. May a four-year period of ineligibility constituting a restriction to athletes’ rights under EU law be justified?

Regarding the final part of the three steps-test, namely justification, the ECJ started in Meca-Medina & Majcen by stating that ‘the compatibility of rules with the [EU] rules on competition cannot be assessed in the abstract.’57 The ECJ continued, while applying general principles set out in Wouters58 to anti-doping rules at issue, that ‘account must first of all be taken of the overall context in which the decision of the association of undertakings was taken or produces its effects and, more specifically, of its objectives.’ (Chapter 2.3.1)59 Consequently, the ECJ stressed that it had to consider whether ‘the consequential effects restrictive of competition are inherent in the pursuit of those objectives (Chapter 3.3.2) (…) and are proportionate to them (Chapter 3.3.3).’60

2.3.1. Does a four-year period of ineligibility seek a legitimate objective?

Despite of some initial doubts, I believe that the fight against doping and the anti-doping sanction in the form of a four-year period of ineligibility seek a legitimate objective.61 Even the ECJ recognized in Meca-Medina & Majcen that the combat against doping follows legitimate aims of ensuring the fair conduct of competitive sport, the need to safeguard equal chances for athletes, athletes’ health, the integrity and objectivity of competitive sport and ethical values in sport.62 However, the question arises as to the legitimate objective sought by a four-year period of ineligibility. In 1990s, the Munich courts ruled in the Katrin Krabbe case that a suspension exceeding two years was illegal.63 Following this decision, the majority of sporting governing bodies reduced a period of ineligibility for the first offence to two years, which consequently withstood scrutiny by several national courts and the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS).64

So why did WADA decide to go for a four-year period of ineligibility? The 2015 WADA Code does not specify the purpose of such a sanction. As mentioned in the introduction to this essay, there was a strong consensus amongst stakeholders, primarily amongst athletes, that intentional cheaters should be ineligible for a period of four years.65 Therefore, we assume that the purpose of the four-year ban is to ensure the effectiveness of anti-doping regulation by, in particular, deterring athletes from using doping and by punishing severely those who eventually cheated. Bearing in mind the importance and general goals of the fight against doping, we consider these aims legitimate. But is it enough to survive potential EU law scrutiny?

2.3.2. Is a four-year period of ineligibility inherent in the pursuit of its legitimate objectives and suitable to achieve them?

I accept that the restrictive effects of a four-year period of ineligibility are inherent in the pursuit of its legitimate objectives. In Meca-Medina & Majcen, the ECJ ruled that penalties are necessary to ensure the enforcement of the doping ban and that their effect on athletes freedom of action must therefore be considered to be, in principle, inherent itself in the anti-doping rules.66 Consequently, a four-year period of ineligibility is inherent in the pursuit of the effectiveness of the fight against doping at both levels, namely the deterrence effect and the severer punishment.

Nevertheless, while a four-year period of ineligibility is suitable to punish a doped athlete more strictly that in the case of a two-year ban, its capacity to deter athletes from taking banned substances is at least doubtful. Firstly, there is no statistical proof that the severity of a punishment actually reduces the violation rates.67 Using criminal law as an example, the effects of deterrence are heterogeneous, ranging in size from seemingly null to very large based on too many variable components to make a general conclusion. Moreover, lengthy sentences cannot be justified on deterrent grounds, but rather either on crime prevention through incapacitation or on retributive grounds.68

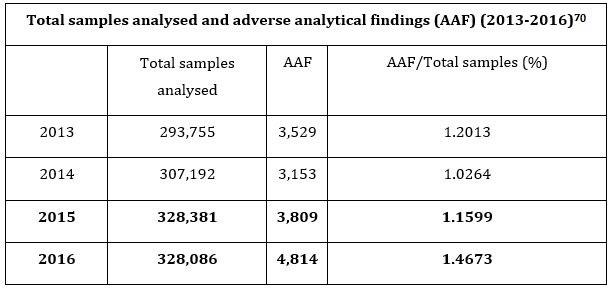

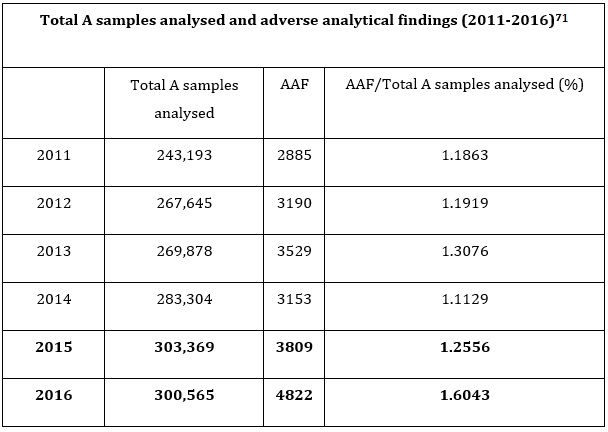

The statistics examining the deterrence effect of a four-year period of ineligibility confirm the increase of the length of sanctions does not mean the decrease of anti-doping rules violations. One contrary, the numbers show the exact opposite. In past two years of the applicability of the 2015 WADA Code and a four-year period of ineligibility, especially in 2016, there was quite a significant increase in the number of adverse analytical findings as well as in the percentage of the ratio of adverse analytical findings to total analysed samples, which denies the announced deterrence effect of a stricter punishment.69

I realize that the aforementioned statistics have only a limited corresponding value with regard to how the announced deterrence effect of a four-year period of ineligibility works in practice. For example, an athlete risks not to be allowed to practice a sport for a whole four-year Olympic cycle, which must have some effect on her or his mind. Moreover, the increase in the number of adverse analytical findings might be caused by advanced methods of testing, analysing samples and evaluating results, as well by other factors. Nevertheless, these statistics necessarily cast some doubts on the desired effect of the ban. Therefore, I am not quite sure that a four-year period of ineligibility has the capacity and is suitable to achieve the legitimate aim of preventing athletes from taking prohibited substances.

2.3.3. Is a four-year period of ineligibility proportionate?

If there are any doubts about the suitability of a four-year period of ineligibility to achieve its objectives, namely to decrease the number of anti-doping rules violations, I argue that the sanction is disproportionate as it goes beyond what is necessary to achieve its otherwise logic and legitimate aims. I submit that a four-year ban is excessive because it prevents athletes from exercising their economic rights and freedoms stemming from EU law for an unreasonably long period of time in the case of their first offence against anti-doping rules. We rather suggest a set back to a default two-year ban, which seemingly reaches the desired goal of doping-free sport in the same way as a four-year period of ineligibility while being at the same time much more athletes’ rights friendly.

The final loss of David Meca-Medina and Igor Majcen in their legal battle against IOC and FINA does not affect the abovementioned conclusion. The ECJ decided that the restrictions, which the threshold of Nandrolone imposed on professional sportsmen, did not go beyond what was necessary in order to ensure that sporting events take place and function properly. The problem was that the swimmers did not specify at what level the threshold in question should have been set at the material time.72 The ECJ added that it could not establish that the anti-doping rules at issue were disproportionate since the appellants didn’t plead that the penalties applicable and imposed in the present case were excessive.73 They didn’t, but anyone else could. So famous former German sprinter Katrin Krabbe did.

In 1995, both the German sports internal tribunal and the Munich courts held that a ban exceeding two years was disproportionate. Firstly, the sports internal tribunal reduced a four-year ban originally imposed by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) on Katrin Krabbe to two years while ruling that ‘the principle of proportionality would require a more flexible determination of the sanction.’74 The Munich District Court decided that a two-year period of ineligibility imposed consequently by the internal tribunal ‘represents the highest threshold admissible under the fundamental rights and democratic principles.’75 Finally, the High Regional Court ruled that a three-year ban consequently imposed by the IAAF ‘was excessive in respect of its objectives.’ The court further noted that ‘such a rigid disciplinary measure as a sanction for a first sport offence is inappropriate and disproportionate.’76

Following the Katrin Krabbe case, the majority of sporting governing bodies reduced a period of ineligibility for the first offence to two years. While it is true that a two-year ban consequently withstood scrutiny by several national courts and the CAS,77 there are authors criticizing even this sanction for its lack of proportionality. They claim that a two-year suspension for a first doping offence is ‘unacceptable in the light of the shortness of a career in several sports disciplines and of the age of several athletes.’78 Nevertheless, I believe that a two-year suspension for a first doping offence is not disproportionate since I agree that a more lenient sanction would be likely to seriously jeopardize the effectiveness of the fight against doping.79

What about a four-year period of ineligibility? Would this ban now withstand the scrutiny of the EU or the EU member states’ bodies and institutions? According to WADA, the four-year sanction for intentional doping enjoys a broad support.80 On the other hand, the former president of the IOC Juan Antonio Samaranch thought that such a sanction was excessive.81 And I think so too. I claim that a four-year period of ineligibility is disproportionate to the legitimate objectives of the effectiveness of anti-doping regulation, in particular the deterrence effect and the stricter punishment of doped athletes. While I believe that the fight against doping is undoubtedly important, I also believe that everyone deserves a second chance. The purpose of every punishment is, amongst others, re-education with the aim of enabling the offender to integrate into society and continue a normal life once the sentence is finished. However, a four-year ban has got devastating effects for the majority of athletes serving it, who will probably never get to compete again. In such cases, a four-year ban materially equals a lifetime ban.

An athlete serving a four-year penalty can’t participate in basically any official competition or sporting activity. She or he can’t train with a team or use facilities of a club or member organization of the WADA Code’s signatory’s member organization. This means that even if the doped athlete wants to practice the sport and be ready again in four years, his or her possibilities are very limited. Moreover, some or all sport-related financial support or other sport-related benefits received by the doped athlete are withheld. The athlete don’t get any public funding and he or she cannot expect private sponsors to support him or her. In extreme cases, such athletes can also have issues with their family, friends or get into a criminal activity. I believe that this is not something that the fight against doping should bring despite of all its positive goals.

From the EU law point of view, a doped athlete serving a four-year period of ineligibility is excluded from the market and cannot engage in any economic activity, at least not as an athlete. For four years, he or she cannot work, provide services as a self-employed person or establish himself or herself in another EU Member State or engage in an economic competition as an undertaking. She or he cannot compete neither at national nor at international level and therefore is deprived of the main source of his or her income. While the fair conduct of competitive sport, equal chances for athletes, their health, the integrity and objectivity of competitive sport and ethical values in sport are undoubtedly important, I claim that a four-year period of ineligibility and its restrictive effects prevail over these legitimate objectives and are therefore disproportionate to them.

Moreover, I argue that a two-year period of ineligibility can achieve the legitimate objectives of the fight against doping in the same way as a four-year ban while being at the same less restrictive to athletes’ rights under EU law. Earlier in this article, I showed that a four-year punishment actually didn’t reduce the rates of anti-doping rules violations compared to eras when a two-year ban was a general sanction. Therefore, a two-year sanction constitutes a measure which is much more benevolent to athletes’ rights under EU law but equally capable of preventing athletes from violating anti-doping rules as a four-year period of ineligibility.

Furthermore, I suggest that WADA as well as other national and international sporting governing bodies should focus on and invest more time and money into prevention rather than into repression. I think that the number of anti-doping rules violations can be reduced much rather by educating athletes in ethical principles of sport and anti-doping than by just threatening them with a devastating sanction. Let’s work with athletes from their young age, let’s try to instil the fair-play spirit into their mind and let’s explain to them the negative effects of using doping for their health. Let’s also work with athletes serving the penalty for anti-doping rules violations so that they are ready to live and compete again as clean athletes. It’s better to spend time, energy and money on preventing the problems that on dealing with their negative effects.

Conclusion

WADA as well as other sporting governing bodies and EU law can coexist under a promising alliance, which is very desirable since the EU bodies and institutions’ decisions clearly influence the global sporting scene. These bodies and institutions take into account the specific nature of the fight against doping, respect anti-doping bodies’ legal autonomy and therefore limit themselves in interfering with anti-doping rules only as long as they breach athletes’ rights under EU law. Nevertheless, I argue in this essay that a four-year period of ineligibility rather turns the relationship between anti-doping bodies and EU law into a dangerous liaison. This sanction is not suitable of decreasing the number of anti-doping rules violations and constitutes a disproportionate restriction on the rights that athletes derive from EU law as workers, self-employed persons or undertakings.

And what about human rights? Doesn’t a four-year period of ineligibility violate the right to liberty and security? What about the principles of legality and proportionality of criminal offences and penalties? Doesn’t this sanction and the process of its imposition interfere with the right to fair trial? Jean-Paul Costa argues that the sanctions contained in the 2015 WADA Code do not violate internationally recognized principles of proportionality and human rights.82 I am not quite sure about it as I believe that some of these sanctions, as well as other anti-doping rules, significantly limit athletes’ rights. The compliance of these rules with human rights of athletes definitely deserves further attention.

Coming back to the EU, WADA and other anti-doping bodies should be more attentive to EU law since a potential ruling of the CJEU holding their rules incompatible with EU law could represent another Bosman judgment flipping the world organisation of sport upside down. Therefore, I seek to balance objectives, interests and values protected by anti-doping bodies on hand, and the rights that athletes derive from EU law on the other hand. I suggest to set the default period of ineligibility for the first doping offence back to two years with the possibility of imposing a four-year ban only in exceptional cases when aggravating circumstances occur. Simultaneously, I recommend to focus on prevention, to work actively with athletes and to educate them in the ethical principles of sport and inform them about negative consequences of doping for their health.

In conclusion, I believe that WADA and other anti-doping bodies should carefully think their moves over in the game of chess against EU law. They play with white pieces. Therefore, they have the right to make the first move. They must simultaneously pay attention to the moves of EU law, notably the case law of the CJEU, and adapt their style of playing to that of their opponent. They are free to establish the sanctions for anti- doping rules violations. At least, unless a court checkmates them.

Autor: Jan Exner83

Poznámky pod čiarou:

[1] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 48; see also European Commission, COMP/39471, Certain joueur de tennis professionnel /Agence mondiale antidopage, ATP Tour Inc. et Fondation Conseil international de l'arbitrage en matière de sport [12 October 2009], paras. 19-27.

[2] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2015, Art. 10.2.1, 10.3.1, Date of publication: 1. January 2015: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti-doping-code.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[3] World Anti-Doping Agency, Significant Changes Between the 2009 WADA Code And the 2015 WADA Code, Version 4.0.1, Date of publication: September 2013: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wadc-2015-draft-version-4.0-significant-changes-to-2009-en.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[4] World Anti-Doping Agency, 2021 WADA Code Review: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/the-code/2021-code-review Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[5] The case of Jan Štěrba, Czech sprint canoeist, provides a nice example of this thin line. On 9 July 2012, the Doping Control Panel of the International Canoeing Federation (ICF) found Jan Štěrba guilty of a doping offence for using beta-methylphenylethylamine. Jan Štěrba was given a 6-month ban, even though the substance, contained in a sport drink, was not listed on the Prohibited List. The panel argued that the substance had a similar chemical structure a biological effect and was therefore prohibited. The ICF Court of Arbitration determined that Jan Štěrba did not commit any anti-doping rules violation and lifted the sanction. Before the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), which ruled on the ICF’s appeal, Jan Štěrba claimed that the substance was not on the Prohibited List and that he could not have known its similar chemical structure and biological effects. Consequently, the CAS found Jan Štěrba guilty of an anti-doping rules violation, but imposed only a reprimand on the athlete who remained eligible to compete in the 2012 London Olympics finally winning a bronze medal in a K4 category.

[6] For example, J. W. Soek argues that the strict liability principle, which is one of the core principles of the WADA Code and the fight against doping, violates the presumption of innocence enshrined in Article 6(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights. See Soek 2016.

[7] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2015, Purpose, Scope and Organization of the World Anti-Doping Programme and the WADA Code, Date of publication: 1 January 2015: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti-doping-code.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[8] Ibid.

[9] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2015, Introduction, Date of publication: 1 January 2015: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti-doping-code.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[10] Costa 2013.

[11] World Anti-Doping Agency, Who we are: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/who-we-are. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[12] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2015, Date of publication: 1 January 2015: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti-doping-code.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[13] Ibid., Art. 10.12.

[14] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2003, Arts. 10.2 and 10.3, Date of publication: 1 January 2004: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada_code_2003_en.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[15] World Anti-Doping Agency, Significant Changes Between the 2009 WADA Code And the 2015 WADA Code, Version 4.0.1, Date of publication: September 2013: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wadc-2015-draft-version-4.0-significant-changes-to-2009-en.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[16] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2009, Arts. 10.2, 10.4 and 10.6. Date of publication: 1 January 2009: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada_anti-doping_code_2009_en_0.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[17] World Anti-Doping Agency, Significant Changes Between the 2009 WADA Code And the 2015 WADA Code, Version 4.0.1, Date of publication: September 2013: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wadc-2015-draft-version-4.0-significant-changes-to-2009-en.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[18] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2015, Arts. 10.2.1 and 10.2.2, Date of publication: 1 January 2015: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti-doping-code.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[19] World Anti-Doping Agency, Significant Changes Between the 2009 WADA Code And the 2015 WADA Code, Version 4.0.1, Date of publication: September 2013: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wadc-2015-draft-version-4.0-significant-changes-to-2009-en.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[20] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2015, Purpose, Scope and Organization of the World Anti-Doping Programme and the WADA Code, Date of publication: 1 January 2015: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti-doping-code.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2017.

[21] Morgan 2015.

[22] As a result of violation of Arts. 2.1, 2.2 and 2.6 of the 2015 WADA Code.

[23] There are two outstanding examples of this. In the famous Bosman judgment of 1995 (CJEU, C-415/93, Union royale belge des sociétés de football association and Others v. Bosman and Others, ECLI:EU:C:1995:463), the Court of Justice (ECJ) hold nationality clauses and transfer fees imposed by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) incompatible with the provisions of EU law protecting the freedom of movement for workers. As consequence, both the UEFA and the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) adjusted their rules to the judgment’s requirements.

In 2006, the European Commission, the Tribunal and consequently the ECJ dealt with anti-doping regulation imposed by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and subsequently adopted by the Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA) in the Meca-Medina & Majcen judgment (CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492). Even though the two swimmers finally lost their legal battle, the judgment is significant as it broadened the group of sporting rules to which EU law applies.

These two cases as well as many other rulings illustrate that the EU institutions’ decisions apply to athletes as EU citizens, workers, self-employed persons and undertakings as well as to sports federations based in the EU or undertaking activities in the EU territory. Moreover, the decisions simultaneously influence whole sporting world since international sporting governing bodies tend to harmonise their rules globally and they do not want to leave Europe as a solitary island applying different regulations.

[24] For a general overview of the application of this test to the free movement of persons and services see Barnard 2016.

[25] This division is nicely illustrated for example in the case CJEU, C-176/96, Lehtonen and Castors Braine, ECLI: EU:C:2000:201. First, the ECJ assesses whether Mr Lehtonen and respective basketball rules fall within the scope of EU law (paragraphs 32-46). Thereafter, the existence of an obstacle to freedom of movement for workers is examined (paragraphs 47-50). Finally, the ECJ engages in exploring whether such a restriction can be justified (paragraphs 51-59).

[26] Exner 2016, p. 15.

[27] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492.

[28] European Commission, COMP/38158, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. International Olympic Committee [1 August 2002], paras. 5,6; CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 3.

[29] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 3.

[30] European Commission, COMP/38158, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. International Olympic Committee [1 August 2002]; CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 3.

[31] European Commission, COMP/39471, Certain joueur de tennis professionnel /Agence mondiale antidopage, ATP Tour Inc. et Fondation Conseil international de l'arbitrage en matière de sport [12 October 2009], paras. 19-27.

[32] European Commission, COMP/38158, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. International Olympic Committee [1 August 2002], paras. 32-55.

[33] CJEU, T-313/02, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:T:2004:282, paras 40 – 41; CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 7.

[34] CJEU, T-313/02, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:T:2004:282, paras. 44 - 47; CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 9.

[35] CJEU, T-313/02, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:T:2004:282, para 69.

[36] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492.

[37] Ibid., Opinion of the Advocate General Philippe Léger, paras. 20, 28; see also Infantino 2006, p. 5.

[38] Infantino 2006, p. 5.

[39] CJEU, C-13/76, Dona v. Mantero, ECLI:EU:C:1976:115, paras. 14, 15.

[40] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 26.

[41] Ibid., para. 26; see also CJEU, C-415/93, Union royale belge des sociétés de football association and Others v. Bosman and Others, ECLI:EU:C:1995:463, para. 76; CJEU, C-51/96 and C-191/97, Deliège, ECLI:EU:C:2000:199, para. 43.

[42] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 27.

[43] Ibid., para. 27 and the following; see also Exner 2016, p. 39; Weatherill 2013b, pp. 401-424.

[44] European Commission, COMP/39471, Certain joueur de tennis professionnel /Agence mondiale antidopage, ATP Tour Inc. et Fondation Conseil international de l'arbitrage en matière de sport [12 October 2009], paras. 19-27.

[45] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 26.

[46] European Commission, Case AT.40208 – International Skating Union's Eligibility rules [8 December 2017].

[47] Statement by Commissioner Vestager on the International Skating Union infringing EU competition rules by imposing restrictive penalties on athletes, 8 December 2017: http://europa.eu/rapid/press- release_STATEMENT-17-5190_en.htm Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[48] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 27 and the following.

[49] Ibid., para. 28.

[50] Ibid., para. 28.

[51] Exner 2016, p. 25.

[52] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 45.

[53] Ibid., para. 54.

[54] Ibid., para. 48; see also European Commission, COMP/39471, Certain joueur de tennis professionnel/Agence mondiale antidopage, ATP Tour Inc. et Fondation Conseil international de l'arbitrage en matière de sport [12 October 2009], paras. 19-27.

[55] SFT, Lu Na Wang et al. v. FINA (5P.83/1999), Decision of 31 March 1999. CAS Digest II, pp. 767, 772; see also Kaufmann et al. 2003, p. 43.

[56] World Anti-Doping Agency, World Anti-Doping WADA Code 2015, Art. 10.12, Date of publication: 1 January 2015: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti- doping-code.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[57] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 42.

[58] CJEU, C-309/99, Wouters and Others, ECLI:EU:C:2002:98.

[59] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 42.

[60] Ibid., para. 42.

[61] I aware of the fact that there is an ongoing discussion regarding the legitimacy of the fight against doping and that not everyone believes that fair sport is worth fighting for. Unfortunately, I have not enough space to cover this particular topic on these limited lines. Nevertheless, I believe that the vast majority of athletes, officials and other sporting actors consider the fight against doping a legitimate and indispensable part of the sporting world. I am one of them.

[62] Ibid., para. 43.

[63] Krabbe v. IAAF et. al., Decision of the LG Munich of 17 May 1995, SpuRt 1995; Krabbe v. IAAF et. al., Decision of the OLG Munich of 28 March 1996, SpuRt 1996.

[64] Kaufmann et al. 2003, p. 44.

[65] World Anti-Doping Agency: Significant Changes Between the 2009 WADA Code And the 2015 WADA Code, Version 4.0.1, Date of publication: September 2013: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wadc-2015-draft-version-4.0-significant-changes-to-2009-en.pdf. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[66] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 44.

[67] Vrijman 2000, p. 158.

[68] Nagin 2013, p. 66.

[69] An Adverse Analytical Finding (AAF) indicates the presence of prohibited substances or methods in a particular sample. AAF should not be confused with adjudicated or sanctioned anti-doping rules violations (ADRV) for several reasons. First, these figures may contain findings that underwent the therapeutic use exemption (TUE) approval process. In addition, some AAFs may correspond to multiple measurements performed on the same athlete, such as in cases of longitudinal studies in testosterone (i.e. tracking the testosterone level of one athlete over a period of time).

[70] World Anti-Doping Agency, Annual Report 2014, p. 33, Date of publication: 20 July 2015; World Anti-Doping Agency, Annual Report 2016, p. 48, Date of publication: 24 August 2017: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/finance/annual-report. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[71] World Anti-Doping Agency 2016 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures, Date of Publication: 25 October 2017: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/laboratories/anti-doping-testing-figures. Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[72] CJEU, C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2006:492, para. 54.

[73] Ibid., para. 55.

[74] Reported in Krabbe v. IAAF et. al., Decision of the LG Munich of 17 May 1995, SpuRt 1995, pp. 162, 166.

[75] Krabbe v. IAAF et. al., Decision of the LG Munich of 17 May 1995, SpuRt 1995, pp. 161, 167.

[76] Krabbe v. IAAF et. al., Decision of the OLG Munich of 28 March 1996, SpuRt 1996, pp. 133, 138; see also Morgan 2015.

[77] Kaufmann et al. 2003, p. 44.

[78] Baddeley 2000, p. 20.

[79] Kaufmann et al. 2003, p. 48.

[80] World Anti-Doping Agency, 2021 WADA Code Review: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/the- code/2021-code-review Date of last access: 23 May 2018.

[81] Wilson et. Derse 2001, p. 312.

[82] Costa 2013.

[83] Ph.D. Candidate at the Faculty of Law of the Charles University in Prague. I am much obliged and I would like to thank Jan Petržela for all his time, advice and valuable comments during the work on this essay. All errors are nevertheless my responsibility. All opinions expressed in this essay are strictly personal.